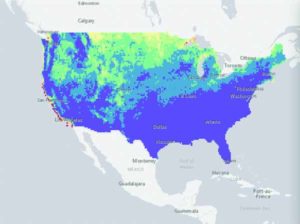

Mapping biodiversity

A new interactive map helps predict where species will move in a warmer climate

A new ESTO-funded technology helps predict when and where pileated woodpeckers, desert pocket mice and white fir trees, among many species, could migrate under future climate scenarios.

Researchers at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, created an interactive web portal that pulls together satellite, airborne and ground-based information, as well as climate projections and ecological forecasts, to determine how one species could impact another as they relocate and compete for suitable habitats.

“We need to consider who’s living with whom in order to understand larger impacts,” said Jennifer Swenson, the project’s principal investigator and a professor at Duke.

The portal, dubbed, Predicting Biodiversity with a Generalized Joint Attribution Model, or PBGJAM, aims to explore how a biodiverse community responds to climate change as a whole to more accurately predict the impact of both the individual species and the entire ecosystem.

To tackle this, the PBGJAM team built on their powerful Generalized Joint Attribution Model, or the latter part of the acronym, which can pull in different kinds of data for multiple species. For instance, the desert pocket mouse and other mice species are currently concentrated in the southwestern region of the U.S. As they start losing viable habitats with climate change, they’ll be forced to move north or east, all while competing with each other for resources and scurrying from new and old predators.

The model considers how many species live in a specific region, how many suitable habitats exist for specific species, how all this could change in the future and how one species’ movements could affect another’s.

Adding the PB to the GJAM makes the approach easier to use for a larger audience, Adam Wilson, a professor at the University at Buffalo, said. PBGJAM provides a web interface that lowers the barrier of entry for decision makers, scientists and any interested individual to get involved. They only need to choose an ecosystem type and then see how it’s shifted, Wilson said.

Elizabeth Goldbaum, March 2020

elizabeth.f.goldbaum@nasa.gov